A

Shift in Powers

By Joshua Kors

The

road from Kuwait to Baghdad was 11 hours. Brian Powers drove nine

of them.

“You're

shit nervous. A war just happened, and you don't know what's going

on. I'd never been in a war zone before. You're looking for anything

threatening. And you don't know what you're looking for. There's

a mass of people and trash everywhere.” This was spring 2003, a

month after coalition troops arrived, before the insurgency had

taken shape.

Powers

was part of the 352nd Civil Affairs Command, deployed to Baghdad

to help reconstruct the city's government: its police and education

department, its banking system, all shattered in the war's crossfire.

What Powers didn't expect is for the city to reconstruct him.

He entered the

Middle East numb, he says, a bachelor, a specialist who in his own

words was still “green behind the ears.” Powers left the Middle

East two years and eight months later without that green shading,

a sergeant whose work caught the attention of the queen of Jordan,

a husband with a daughter on

the way. |

|

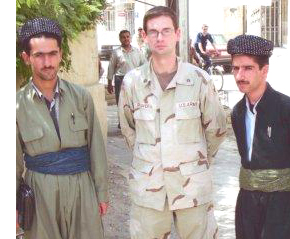

During

his service in the Middle East, Sgt. Brian Powers worked to understand

Muslim culture and connect with the locals. "When you

win them," he says, "that's when you win."

|

|

“Wrong

Strategy, Wrong Tactics”

Back

in the States, Powers was a research assistant at a Washington law

firm. A year later, in Baghdad, he was a bodyguard, assigned to

protect a lieutenant colonel who was working to keep the Ministry

of Education running. The provisional authority was determined to

keep Baghdad University up and running, to maintain a “sense of

normalcy, even though some of the buildings had no electricity,

no windows, there were fires, and garbage strewn all over the place

from looting.” Powers says at first, the students were extremely

grateful for the effort, and they approached him with gestures of

friendship.

That

didn't last. Within months, says Powers, the system began breaking

down. It started with the payroll.

Powers'

unit was assigned to make sure Baghdad's police officers got paid.

But the city had no functioning credit system, and the banking system,

he says, was barely stable. So police payments were made in cash,

by hand. “We'd go to the bank, withdraw three-quarters of a million

dollars, drive across town and dole out the money to the police

captains.” Chunks of cash that large brought out the worst in everybody,

says Powers, and the safeguards to make sure the captains took the

right amount of money — or that the money got where it was supposed

to go — were essentially non-existent. “You never got a straightforward

answer from the Iraqis. ‘You say you have 100 guys? Okay, here's

the money for 100 guys.'” Time after time Powers' unit would just

take the captains' word for it.

“We

did our job with due diligence, but it was all freewheeling cash.

The lack of a coherent policy — even an 8th grader would have realized

this is not the best way to do it.” Powers says that if they had

more boots on the ground, his unit could have made sure the money

got where it was supposed to go. But they didn't, so they couldn't.

The

sergeant adds that from his vantage point, the Iraqi police captains

weren't the only ones with their hands in the military till. He

points to Titan Corporation, a San Diego-based defense contractor

with annual revenues of approximately $2 billion. In 2003 Titan

signed a contract with the U.S. government to provide translation

services for $112.1 million. But on the ground in Baghdad, says

Powers, his corp was repeatedly without translators. Powers says

the translators he did work with were making “next to nothing”:

$20 a week. They were given no benefits and on dangerous missions

were provided out-of-date body armor.

Powers

recalls one female translator who was struck by shrapnel from an

IED and died shortly thereafter. “The sad thing about that,” he

says, “she and an American soldier in my unit had a romantic involvement.

They were going to get married after the war.”

At

that, Powers pauses for a moment, reflecting on how the Iraqi operation

turned sour. In the end, he says, it wasn't just the Iraqi police

or the Pentagon's contractors. It was the military's whole approach

— “the wrong strategy and the wrong tactics.” “Our strategic planners

didn't understand we were facing an insurgency,” he says. “They

confronted it as an opposing army, kicking in doors, making enemies

from all the people.”

“The

goal should have been to win the hearts and minds of the people.

When you win them, that's when you win — especially in a foreign

land, in someone else's country, when you don't understand the culture.”

Powers says he can't believe the military didn't take that lesson

from Vietnam.

But

apparently it didn't. Three decades later coalition forces entered

Iraq without understanding Muslim culture and, says Powers, without

even attempting to understand. The sergeant speaks of troops who

slipped their translators some pork, then mocked them for eating

the forbidden meat. “I remember a young soldier grabbing an old

woman out of her car. She was in her mid-50s, maybe 60s. He grabs

her and yanks her out of the car. It's a great offense to grab a

woman there. And it was clear she didn't speak English. And of course,”

notes Powers, “we didn't have a translator to speak to her in Arabic.”

By

summer 2003 the good will that greeted the sergeant and his civil

affairs unit was beginning to collapse. In July he dropped by a

Baghdad market with some fellow soldiers. Powers had his guard down.

Everybody did, he says. One of the soldiers wandered away from the

group to look at some music CDs. “It was a split second,” says Powers,

his voice a bit clenched. “You open up for a split second — and

you learn.”

An

Iraqi put a pistol to the back of the soldier's head and fired.

The bullet came out his cheek. Incredibly the soldier survived.

But he's now a quadriplegic and has lost higher brain function.

“That

really brought it home. Because before that everything was calm.

We'd been there a few months, and nothing had really happened. We

thought, ‘Oh, this is safe.' But the insurgency was just taking

shape.” After that, Powers and his unit became suspicious of everything.

The violence, he says, crept into his thoughts. “You start thinking,

‘A suicide bomber can walk right in here and kill 50 people.' You

don't know who's out there to kill you.”

“It

became really acute. You felt insecure everywhere.”

Powers

says his unit responded to that insecurity with clenched, powerful

faces, masks of authority they took on patrol with them. Initially

the sergeant did the same. The reaction he got from the students

at Baghdad University was remarkable. “The students stopped talking

to us — first, I think, out of hatred, then out of a sense of fear.”

Powers, the skinny, spectacle-wearing military man, kept up that

facade until one day, a student approached him and deflated the

act.

“He

said, ‘You don't look like you could kill anybody. You look like

a doctor.' And that was great because after that I never tried to

put that mean face back on. After that, I put my smile on, and people

started coming up to me again. There were other soldiers to wear

the mean faces, kick in doors and stuff.”

“To

this day I'm convinced that saved me from being shot at a few times,”

says Powers. “People didn't shoot us because they knew us. They

saw we were treating them with respect. I saw an interview on TV

with kids saying they didn't shoot soldiers who they knew, the ones

who were nice to them.”

Traffic

at the Border

In

January 2004, after nine months in Baghdad, Powers was shipped 350

miles west of the capital to a desert that divides Iraq from Jordan.

It's a line on a map the British drew, one Iraq and Jordan redrew

a few years ago, and says Powers, if the border weren't there, there'd

be nothing — just bleak stretches of sand as far as the eye can

see. “It was like the desert from ‘Star Wars.' Sand, rock and nothing

else. When the wind would kick up, you'd get a sandstorm. Sometimes

it was so bad it would blot out the sun.”

|